“Haiti has so many doctors!” …and other blasphemies

February 2, 2018 |

Haiti is a photogenic land of rugged mountains, beaches, colour, and astounding beauty. But the symptoms of the country’s desperate poverty are many, and obvious as soon as I cross the border: buildings in disrepair, rubbish lining the streets, contaminated rivers. The locals are acutely aware of these problems, and their views range from world-weary cynicism (“I haven’t voted in twenty years”) to cautious optimism (“I think Haiti will be very different in twenty years”).

It is far and away the most commonly visited country in the Western hemisphere by medical volunteer groups, accounting for 123 organizations in our directory. The government registry of Haitian development NGOs of all types, meanwhile, is over 270 pages in length.

Travel through Haiti is endlessly interesting. The road is bumpy from the Dominican border to Cap Haitien, and the driver manages to squeeze 23 passengers into our tiny van. The door of the van falls off as he tries to close it.

A day later, I am traveling again. The road from Cap Haitien to the village of Bas Limbé is potholed and broken, right up until it ceases to exist. On the way, we pass countless women with food and other sundries skillfully balanced on top their heads. We’re passed by tap-taps, more or less the Haitian version of an Uber pool.

“They’ve had that name for a long time” responds Dr. Roosevelt Pierre when I ask him where their name came from. “I think maybe because you have to tap tap to pay your money.” He demonstrates by tapping me on the back. Later, someone contradicts him and tells me that it’s the sound of the passengers tapping on the roof to tell the driver to stop.

The healthcare system in Haiti

The private clinics scattered all over Cap Haitien charge anywhere from 1000 to 1500 gourdes ($15 to $20 US). At a government clinic, you might be charged only 600 gourdes, but that’s before paying for everything else, including your medications and any supplies, dressings, or tests associated with your care. On top of that, “the service is not too good”, according to Roosevelt.

No surprise, then, that NGOs have cobbled together a parallel healthcare system of their own. It recognizes the poverty of ordinary Haïtiens. In the village of Bas Limbé, for example, the locals are served by a government clinic, a Catholic NGO, and Haiti Village Health, which operates a free clinic staffed by Haitian physicians two days a week. Visiting American brigades arrive to help every two months.

Who pays? Who can pay? And who should pay?

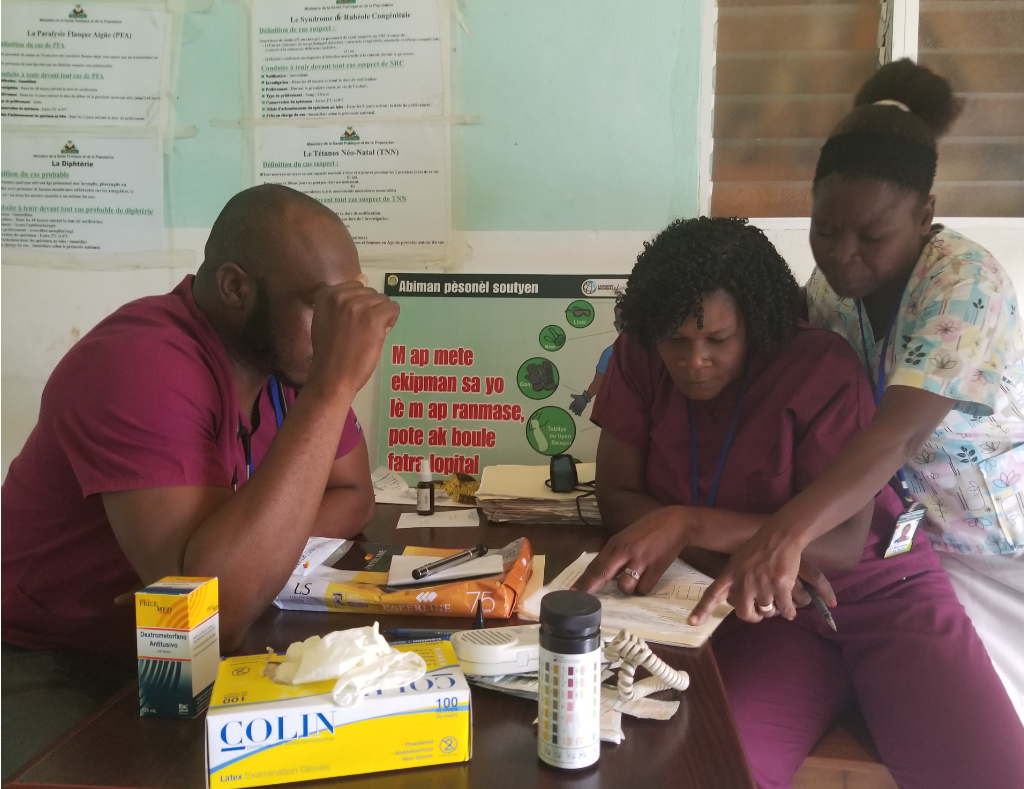

As the saying goes, communication is 90% body language. But despite their enthusiasm, my limited French doesn’t take me far towards understanding the end of day medical staff meeting in Kreyol. Dr. Roosevelt translates for me at the end.

As it were, the meeting ended up being mostly the medical staff complaining about the 100 gourde ($2 US) administration fee that the clinic charges for the charts. The patients resent having to pay it. “Why?” I ask. “Is the problem that they can’t afford it?”

“They think it’s their property!”

“Bienvenue à Canada!” I say dryly. It gets an easy laugh, but obviously the issues are more complicated. Paul (my guide in Bas Limbé) has a profound appreciation for the work that volunteer brigades do in providing care to Haitians whose poverty shuts them out of the healthcare system.

But shortly after saying this, he also notes that Haiti has “so many doctors”. This claim would be disputed by the World Bank and World Health Organization. But he notes that with the unemployment rate over 70%, most Haitians are driven into the informal economy or driving motorcycles for a living, no matter their qualifications. It is often as difficult for those doctors to find work as it is for everybody else in Haiti. It is a complaint that I hear repeatedly during my visit. I’m torn.

Are medical volunteers unfair competition for local doctors?

On the last day of my stay in Bas Limbé, an American pediatric team from Hands Up for Haiti arrives at the guest house. They will be running mobile outreaches every day this week. Usually, Monday is the busiest day at the village clinic in Bas Limbe. But this Monday is unusually quiet. Dr. Roosevelt and I only see fifteen patients. The next clinic day is the same. Usually, they come from the villages to the main clinic, but these days, the clinics come to them.

“They have better access now.” Dr. Roosevelt comments when I ask him about this.

On one hand, NGOs may well be serving those who cannot afford private clinics, or in more remote parts that indeed desperately lack access. But on the other, who would choose to see a local physician when volunteers are giving away the same service for free next door?

Next: All roads lead to Guatemala

Register

Sign up for free to flag trips of interest and email organizations directly through our directory.

Comments

0 comments